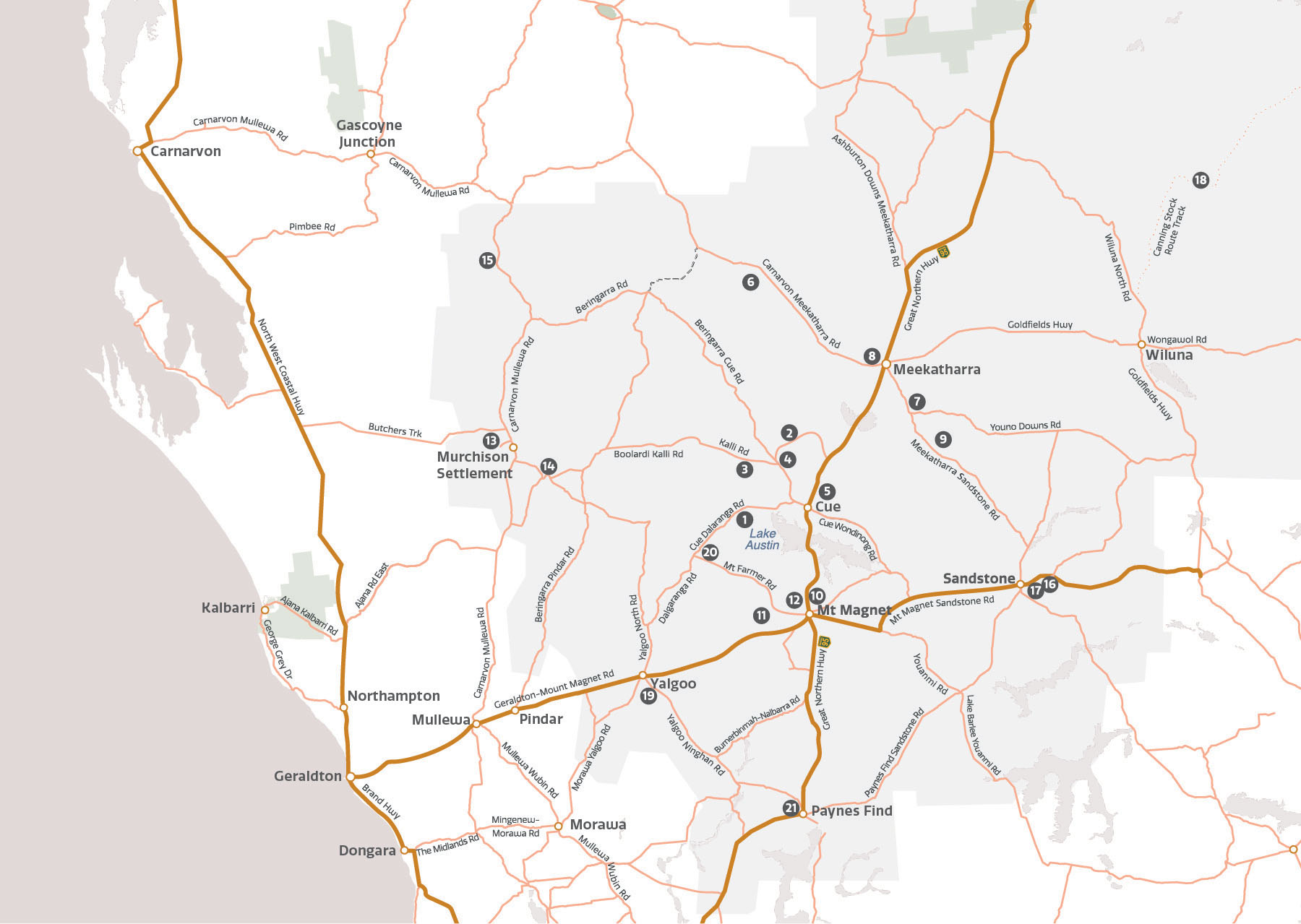

Site map and Murchison GeoRegion site info

Walga Rock, also known as Walgahna, is arguably Australia’s second largest monolith after Uluru and is a site of deep cultural and spiritual significance to the Wajarri Yamatji people.

Covering about 50 hectares, this 2.6 billion year old monzogranite has eroded in parts to form a series of rock overhangs which provided shelter and protection from the elements.

The A – B – C of Walga Rock

Abiotic: Exposure to the elements has weathered Walga Rock into the shape you see today with cracked slabs and ‘devil’s marbles’. Rock pools dot the top of the rock and fill when it rains and water runs down the sides of the rock, leaving trails in its wake.

Biotic: The dense vegetation at the base provides shelter for birds such as Western Bowerbirds, Red-back Kingfishers and Slaty-backed Thornbills. It is also a resting point for kangaroos, goannas, snakes and emus.

Cultural: The Aboriginal rock paintings at Walga Rock are believed to be 9,000 years old. Walgahna served as a meeting place for Aboriginal people coming from across Australia and the rock overhangs provided shelter from heat and storms. One of these shallow caves contains more than 980 motifs depicting snakes, emus, kangaroo tracks and hands drawn with ochre from Wilgie Mia and white clay tones from the nearby breakaways. Look out for a painting of what appears to be a square-rigged sailing ship, it’s origin has been baffling people for nearly 100 years.

Walga Rock holds great significance to the Wajarri Yamatji People and visitors are asked to show respect for the site.

Wilgie Mia holds great significance to the Wajarri Yamatji People and is a protected Aboriginal Heritage site. Under the Aboriginal Heritage Act, it is prohibited to enter Wilgie Mia without permission. For more information please contact the Cue Visitor Centre.

The A – B – C of Wilgie Mia

Abiotic: Known also as Thuwarri Thaa – The Place of Red Ochre – Wilgie Mia holds the honour of being the largest and deepest underground Aboriginal ochre mine in Australia. Ochre is a natural earth pigment containing iron oxide and was formed in the Weld Range millions of years ago. It comes in various colours including red, yellow and green.

Cultural: Ochre was and still is an important part of Aboriginal culture used in ceremonies, medicines, and rock and body paintings. The red ochre from Wilgie Mia was traded across Australia as far as Ravensthorpe, the Kimberley and Queensland, as well as into Indonesia in what is believed to be the first example of international trade.

Poona is the home of WA emeralds and the highest quality emerald deposit in the State but there is not enough to sustain large-scale mining.

The A – B – C of Poona

Abiotic: The Poona emeralds are found within the greenstone belt in association with quartz veins with margarite and topaz. (Greenstone belts contains sedimentary and volcanic rocks that have been heated and pressurised after having been deposited on a sea bed. This process, known as metamorphism, produces a greenish hue due to the presence of minerals such as chlorite.) High quality emerald finds are very rare as the gem is often too pale in colour. Most valuable finds measure less than 2 cm long and 1 cm in diameter – but that hasn’t stopped people mining here over the past 100 years.

Visits to Poona are by arrangement only and a Miner’s Right is required for fossicking and prospecting which must be obtained from the WA Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety.

Please contact the Cue Visitor Centre for more information.

Rest a moment at Afghan Rock and follow in the tradition of gold rush cameleers between 1894 and around 1905.

This easily accessible granite outcrop measures about 100m across and rises to 447m above sea level. A well at the site made it a popular stop for Afghan cameleers transporting their wares across the parched and unforgiving Murchison. While the cameleers’ trade has ended, it continues to be a watering hole for wildlife with the natural pools fed by rain and the nearby Berring Creek through most of the year.

The A – B – C of Afghan Rock

Abiotic: Afghan Rock was formed from magma that solidified underground about 2.7 billion years ago before it was eroded to its present level at the surface. Made of monzogranite, an igneous (intrusive) rock composed mostly of quartz and feldspar, it is part of the Archean Yilgarn Craton, which extends from the Murchison past Kalgoorlie in the east.

Biotic: Weathering moulded the surface of this 100 m wide rock outcrop and formed natural pools fed by rain and Berring Creek. The pools, known as gnammas, are an attractive watering hole for birds and mammals such as honeyeaters, thornbills, emus and kangaroos.

Cultural: During the gold rush at the end of the 19th century, teamsters sunk a series of wells with about a day’s ride – or 32 km – between them. These camel wells were built at every third well that the teamsters used and Afghan Rock was one of them. Despite being referred to as Afghans, the cameleers came from a variety of countries including Pakistan, India and Afghanistan though they shared Islam as their religion.

Take a packed lunch and visit the site of former gold rush market gardens at Garden Granite Rock.

Garden Granite Rock rises about 20m above the sandplain and has a circumference of 1km. At approximately 2.6 billion years old, this monzogranite was formed from molten rock that cooled and solidified within the Earth, and was then uplifted and eroded over millions of years. While it’s hard to imagine today, Garden Granite Rock was once the site of one of a number of market gardens in and around Cue, established in 1894 to supply the gold rush population with fruit and vegetables.

The A – B – C of Garden Granite Rock

Abiotic: As you walk over the rock, look for white/pink crystals dotted in the surface. These are known as feldspar crystals and are clearly visible in the orange granite.

Cultural: “Garden, The Granites” was registered as the 19th market garden in Cue with James Truss and James Hunter listed as working the gardens in 1894 and 1895. A well was sunk in 1896, which would have been a great boon for the growers. Market gardens were an important part of providing food to gold rush settlements.

Garden Granite Rock has areas of cultural significance and visitors are asked to show respect for the site.

Zircon crystals found at Jack Hills, 130km west-north-west of Meekatharra, are about 4.4 billion years old making them the oldest material substance ever found on Earth (Earth is about 4.54 billion years old). Their discovery has helped shape our understanding of the Earth’s early development.

While the zircon crystals are small, Jack Hills and its 500m high neighbour Mount Narryer are much bigger and also home to hardy scrubland, lizards, goannas, snakes, kangaroos and birds.

Access to this site is restricted (for scientific purposes only) due to the need to preserve the outcrops. Please visit the Meekatharra Community Resource and Visitor Centre to learn more about Jack Hills.

Mount Yagahong stands 150m above the surrounding landscape, a beacon in an otherwise flat land.

Mount Yagahong’s soil and elevation provides fertile ground for over 70 species of native plants including bush tucker such as the wild pear or cogla (which can be eaten like an apple or cooked like a potato), the mulga with its edible gum or seeds for grinding into an edible paste, or the curara tree whose seeds can be turned into flour.

This bounty brings animals such as goannas, birds and bardi grubs and also makes it an important site for the Yugunga-Nya people and they ask that you respect the sacred nature of the site and avoid climbing the mount or driving around it.

The A – B – C of Mount Yagahong

Abiotic: Made of sandstone and siltstone, Mount Yagahong is relatively young – between 2.1 and 1.6 billion years old compared to the much older rocks of the Archean Yilgarn Craton that it sits upon, which are 2.94–2.63 billion years old.

Biotic: Keep a look out for native animals and bush tucker as you explore the base of Mount Yagahong. The abundance of animals and plants made it ideal hunting grounds for the Yugunga-Nya people as well as an important sacred site.

Cultural: Important Aboriginal sacred site that is a source of many cultural tales. One of the traditions that the Yugunga-Nya share about Mount Yagahong is its importance to their dreamtime stories, or djugurba as it is known in the Meekatharra area. According to Yugunga-Nya legend, the stratified rocks of the hill is said to resemble an emu lying down, its side torn away after a dingo attack.

Connected to Mount Yagahong are the two smaller hills to the east known as Little Bungoo and Big Bungoo. These two hills are known as the little emu chicks that follow behind their father.

Mount Yagahong is a site of cultural significance to the Ugunga-Nya people and visitors are asked to show respect for the site.

Peace Gorge’s scattered piles of golden granite boulders have made it a special place for locals and visitors alike.

Once called the Devil’s Playground, these stunning rock formations and large boulders were chosen as the site of a picnic that celebrated the end of the First World War in 1919. Since then it has been known as Peace Gorge. It’s not just a popular spot for visitors but also for native wildlife drawn there for the food and shelter but you’ll be drawn to the tranquil surroundings and the stunning view, particularly at sunset.

The A – B – C of Peace Gorge

Abiotic: The stunning rock formations and large boulders of Peace Gorge are part of the Chunderloo Monzogranite, which is approximately 2.6 billion years old. Formed from the melting of older rocks at extremely high temperatures which then intruded under great pressure into the Earth’s upper crust, the monzogranite then uplifted and eroded into the shapes you see today. Some of the boulders are in the same orientation they were in when they emerged, while others have fallen victim to gravity. Collection of large rounded, golden granite boulders scattered in piles.

Biotic: Look out for birds such as honeyeaters, thornbills and emus, as well as geckos, lizards and kangaroos. They are drawn here for the food and shelter available from a wide variety of Acacia and Eremophila,

Cultural: The gorge was once known as The Devil’s Playground but when World War I ended in 1919, the Meekatharra Road Board organised a gala picnic and sports day for the returning soldiers. Since then it has been known as Peace Gorge and has become a favoured spot for locals and visitors alike.

The Daily Telegraph, 11 July 1919: Saturday, 19th July 1919, will be the most momentous day of our lives, for it is to celebrate our thankfulness for the victory of right over might and the end of pain and sorrow and strife. … Meekatharra is to take fitting part in that celebration and a real holiday is being prepared by the Peace Celebrations Committee. … [A]n excellent site has been discovered, a mile and 3 quarters out of town, among the granites. It is an ideal and picturesque spot, once known as “The Devil’s Playground” and now to be designated as “Peace Gorge.”

Barlangi Rock is centred on one of Australia’s 27 confirmed meteorite craters.

Formed when a meteorite slammed into the Earth about 2.23 billion years ago, the meteorite’s impact violently altered the landscape and smashed a massive hole in the ground, creating the Yarrabubba Impact Structure. The granite outcrop that is Barlangi Rock rises 30m out of the ground.

Despite an initial diameter of between 30 and 70km, and a severe shock to the Earth, evidence of the impact isn’t immediately easy to see. But it’s there if you know what to look for.

The A – B – C of Balangi Rock

Abiotic: A huge amount of heat and energy was released at the point of the meteorite impact and melted the rock. This molten material then solidified and, following millions of years of weathering and erosion, created the mound of granite that you see today.

The rock that forms Barlangi Hill is the Barlangi Granophyre, a term used to describe a finegrained rock containing small, visible crystals of quartz and alkali feldspar. Other pieces of evidence that point to Barlangi Hill’s violent beginnings include shatter cones, xenocrysts and xenoliths.

- Shatter cones (“conical impressions”) appear in rocks that have been subjected to high pressure shocks.

- Xenoliths (“foreign rock”) are rock fragments that are broken off from the surrounding rock and were enveloped by the molten material generated by the impact.

- Xenocrysts (“foreign crystal”) are similar but are crystals like quartz and feldspar instead of rock.

Please do not collect shatter cones.

The magnificent breakaways of The Granites share a connection with the Badimia people that stretches back 20,000 years.

With driving, cycling and walking trails and picnic sites, these granite outcrops rise to 20m and are spread over several hectares. Erosion has sculpted the soft white granite beneath the laterite to form ridges and caves and huge rounded boulders.

The A – B – C of The Granites

Abiotic: After crystallizing/solidifying deep within the Earth’s crust about 2.7 billion years ago, tectonic forces brought the granite to the surface. The Granites outcrops today are spread over several hectares and reach 20 m high. Weathering over many millions of years has formed a hard red-brown, iron-cemented capping (also known as laterite), while the soft white granite underneath is worn away to form ridges and caves punctuated by piles of boulders.

Look out for Feldspar crystals, rectangular in shape and whitish/pink in colour which are still clearly visible on the capping as they catch the light.

Biotic: The Granites make for attractive shelters for a range of native animals including Sand Goannas (guwiyarl), Red Kangaroos (marlu), Emus (yalibirri) and Echidnas (gunduwa). The Granites are also surrounded by native plants, including Saltbush (Atriplex spp.) and Mulga (Acacia aneura), that not only provide food for animals, but are also a resource for the Badimia, the traditional owners of the land.

Cultural: The Granites is a place of ancient history, not only in the stories the rocks tell but also of the connection to the Badimia people who performed ceremonies here for thousands of years. The Badimia have had a presence at The Granites for at least 20,000 years. Rock art dating to 9,000 years ago of wallaby and emu tracks and hand prints feature on some of the granite walls.

The Granites hold great cultural significance for the Badimia people and visitors are asked to show respect for the site.

Orbicular granite is only found in a few locations around the world – and one of them is on Boogardie Station.

This rare and attractive type of granite rock features light-grey todark-grey orbs that measure 5–15cm across. Each of the orbs is made up of fi ne-to medium-grained minerals including hornblende, biotite, plagioclase feldspar, opaque oxide and titanite. The rarity of this rock and ability to take a hard polish makes orbicular granite highly prized for ornamental masonry. The site is also home to two bald granite rocks – Warroan Rock and Two Rocks – which dominate the landscape. While they’re obvious drawcards, keep an eye out for the pebble-mimic dragons, which are small lizards that resemble stones, as well as the purple, yellow and green of flannel bush along the roadsides.

Permission is essential to access the Boogardie Orbicular Granite, which is located on private property and mining lease. Advance tagalong tour bookings essential. Contact Paul Jones on 0427 634 187

The A – B – C of Boogardie Orbicular Granite

Abiotic: The granite is hosted by a pink, late Archean granitic rock (2.5-3 billion years old) and is one of a few orbicular granite localities known worldwide. This Boogardie Orbicular Granite is about 2.7 billion years old and was most likely formed as a segregation of magma from a larger body. The orbicules are up to about 15 cm across and usually contain five to seven well-defined concentric layers, composed of a number of minerals. Their rarity and ability to take a hard polish makes orbicular granite highly prized for ornamental masonry. This iconic rock is found on every continent, including Antarctica, but only in small quantities.

Biotic: If you visit Boogardie, keep an eye out for keep an eye out for the Pebble-mimic Dragon (Tympanocryptis pseudopsephos). As its name suggests, this small lizard’s dark reddish-brown body resembles that of a stone and its black and white banded tail looks like a dead twig. Measuring up to 7 cm long, it relies on this camouflage to avoid predators among the rocky ground.

Cultural: Boogardie Station is a pastoral lease that includes the Boogardie Quarry and was established by the Jones family in about 1880. The ghost town of Boogardie (an aboriginal name), also known as ‘Jones Well’ was gazetted in January 1998.

This beautiful ridge of granite soars above the surrounding landscape and is particularly beautiful in the glow of sunset.

Weather and erosion have worn parts of the granite rock away to create caverns and caves and these shelters have provided a safe haven for countless animals over thousands of years including ones that have become extinct such as the lesser stick-nest rat.

The A – B – C of The Amphitheatre

Abiotic: There is evidence to suggest the Amphitheatre was the site of an ancient waterfall. The unusual ‘dip’ in front of the rock face is not seen at other eroding breakaways, suggesting the presence of large volumes of water over time.

Biotic: The many holes and tunnels in the Amphitheatre’s face make it a popular place for animals including birds of prey, honeyeaters, bungarra and kangaroos (bigurda – the Badimia name for the kangaroo that inhabits the area).

Cultural: Evidence of animals past and present can be found at the Amphitheatre in the form of cave bitumen or amberat, which looks like hardened tar and collects in dry protected rock areas. An Afghan cameleer known as Goolam Badoola, who founded Bulgabardoo Station (later Meeline) in 1912, used to collect amberat, citing its strong healing properties. Although the locals shrugged it off as bat dung, amberat is sold in India as an Ayurvedic medicine.

Errabiddy Bluff’s steep rocky slopes rise up to 100m high and can be seen from over 30km away.

Errabiddy’s name comes from a Wajarri word meaning ‘mouth of bucked teeth’ and when you see the teeth-like rocks, you’ll understand why its name is so well suited. The large sandstone formations make it an excellent picnic spot and a drive to the top of the hill opposite Errabiddy Bluff provides a great picnic spot and a spectacular view.

The A – B – C of Errabiddy Bluff

Abiotic: Errabiddy Bluff is about 600 million years old and consists of feldsphatic sandstone and siltstone deposited in a shallow basin. The rocks in the area have been folded and uplifted and extensively silicified (replacement of dolomite with silica) which has created a hard surface that is resistant to erosion and protects the softer siltstone and sandstone beneath. Errabiddy is part of the Woodrarrung land system, which features rugged sandstone ranges up to 100 m high with steep, rocky slopes and boulder strewn valleys and gorges. It is found only on Wooleen, Muggon, Yallalong and New Forest stations.

Biotic: Because of its unique formation, Errabiddy is home to a population of Gascoyne or Spreading Gidgee (Acacia subtessarogona) – a tall tree usually only found north of Carnarvon, some 530 km north-west from here. This wattle grows in the gorges in and around Errabiddy. Many other native plants grow on and around Errabiddy Bluff such as Grevillea deflexa, three-winged Bluebush (Maireana triptera) and Warty Fuchsia Bush (Eremophila latrobei).

During wildflower season, Errabiddy Bluff is ablaze with colour, attracting many different birds and mammals such as Black-faced Woodswallows (Artamus cinereus), Grey-crowned Babblers (Pomatostomus temporalis) and Red Kangaroos (Macropus rufus). Its rocks also make great heat pads for geckos, lizards and snakes.

Cultural: Unsurprisingly, Errabiddy Bluff’s unusual appearance and high position on the landscape has made it an important site for Wajarri people, it is part of a Wajarri songline (a traditional song or story recording a journey made during the Dreamtime) that takes in the Murchison River, Wooleen Lake and Budara Rock.

Stand on the shores of one of Australia’s few inland freshwater lakes.

The release of geological stress along the Mount Narryer fault some 60,000 years ago altered the flow of three rivers – the Murchison, Roderick and Sanford, leading to the creation of Wooleen Lake. This 5,500-hectare land system receives water on average only once every four years, fills once every 10 years and overfills once every 30 years.

Wooleen Lake is only accessible to guests of Wooleen Station or visitors who pay a daily access fee. Please contact (08) 9963 7973 for further information or bookings.

The A – B – C of Wooleen Lake

Abiotic: Wooleen Lake is one of the few inland freshwater lakes in Australia. The release of geological stress along the Mount Narryer fault, earthquakes and tectonic forces changed the landscape, creating hills, valleys and channels such that water was diverted and captured in two lakes joined at the neck creating Wooleen Lake.

This floodplain lake on average only receives water once every four years, fills once every 10 years and overfills once every 30 years. Though water doesn’t go into it frequently, when it does, it takes about 10 months to drain. The water fills from seasonal rains in summer and autumn and from the Roderick River when it runs. The water then drains into the Murchison River.

Biotic: When Wooleen Lake is dry, it’s covered in a native grass known as Sporobolus mitchellii that grows up to 60 cm high. Over 140 bird, 60 reptile, 14 mammal, four fish and six frog species are known to visit Wooleen Station and Wooleen Lake for food, water, shelter and breeding. It’s a major nesting site and attracts thousands of birds including the threatened Gull-billed Tern (Gelochelidon nilotica) and Australia’s rarest waterfowl, the Freckled Duck (Stictonetta naevosa).

Cultural: The Wajarri Yamatji people have inhabited Wooleen for tens of thousands of years and it remains significant to their culture today. The lake itself is part of a Wajarri songline, which also includes Murchison River, Errabiddy Bluff and Budara Rock. As well as its spiritual significance, the lake also provided food and water to Wajarri, and there are a number of protected sites around the lake and on Wooleen Station.

Europeans founded Wooleen Station in 1886 to run sheep and cattle using the lake to water their stock. The land degraded over the following century but the current owners of Wooleen Station are working to reverse this trend and return Wooleen to its former glory.

One of only a few permanent water holes on the seasonal Wooramel River, Bilung Pool makes a great spot for bird-watching.

The Wooramel River carved Bilung Pool out of the red ochre on its 363km journey towards the coast. Bilung Pool holds water all year round and during heavy rains a small waterfall tumbles into the pool, which is surrounded by white-barked river gums.

The A – B – C of Bilung Pool

Abiotic: The Wooramel River only runs on the surface only 2-3 times a year for a couple of weeks at a time and as such is known as an ephemeral river or upside down river. The river rises near McLeod Pyramid over 300 kilometres away and as it flows is joined by six tributaries before discharging into the Indian Ocean.

Biotic: Bilung Pool’s permanent supply makes it a place of rest and renewal in an otherwise arid environment. White-barked river gums surround the pool, while plentiful birds, mammals and reptiles are drawn to the promise of water or prey on which to feast. About 50 bird species visit the area around Bilung Pool including honeyeaters, woodswallows, wedge-tailed eagles, swallows, fairy-wrens and finches.

Cultural: Bilung Pool is a significant Aboriginal site and is a sacred place for Wajarri people who know it as Birlungardi and consider it the site of their bimada – the place from which ancient Dreamtime laws and customs originate. The Wajarri believe Birlungardi is the resting place of the Gujida (Rainbow Snake) and throw sand into the water to appease the snake and show it respect –visitors are advised to do the same.

Following European settlement, Bilung Pool became an important stop on the Mullewa–De Grey Stock Route as drovers spent months bringing cattle and sheep from De Grey and Ashburton areas to markets at Mingenew and Mullewa.

Bilung Pool is an area of cultural significance and visitors are asked to show respect for the site.

Come see this spectacular natural stone bridge – before it falls down.

London Bridge has been a popular destination for sunsets, stargazing and picnics for more than 100 years as visitors come to admire its unique shape. Back in the early days of Sandstone’s founding, the bridge was wide enough for a horse and buggy to cross. However, erosion and weathering continue to wear away the laterite and the bridge is getting thinner.

We do ask for your own safety and to preserve this natural wonder that you enjoy the view from ground level.

The A – B – C of London Bridge

Abiotic: This London Bridge was never used as a river crossing but instead was carved out of the rock thanks to wind and rain. It is part of a longer breakaway formed in laterite which overlies rocks estimated to be greater than 2 billion years old stretching for about 800m and varying in height from 3–10m.

Biotic: The breakaway surrounding the Bridge, with its natural caves and crevices provides shelter and homes animals including bungarras, kangaroos, lizards, geckos, eagles, emus, honeyeaters and finches. If you’re lucky, you might even spot a bush turkey. Mulga (acacias), emu bush and ruby saltbush are just some of the flora surrounding the Bridge. At certain times of the year many of the plants will give you a show of beautiful flowers.

Cultural: London Bridge’s unique shape has made it a popular tourist spot since the days of Sandstone’s gazetting in 1906 and was the scene of many large and happy picnic outings, particularly after the establishment of The Brewery nearby (another Murchison Geo Region site). In the early days the bridge was known as “Devil’s Arch” and is still a fantastic place for a sundowner and to watch the spectacular outback sunsets.

Please do not climb or walk on the bridge.

What lengths would you go to for a cold brew?

The Black Range Brewery was constructed in 1907 by Irishman J V Kearney, to provide for the demands of the many miners then working in the area. With the opening of the railway line in 1910, regular supplies of beer from elsewhere became available and broke the brewery’s monopoly. The tunnel is all that remains

The A – B – C of The Brewery

Abiotic: The Brewery was built on top of the laterite breakaway, and the tunnel walls consist of laterite, an iron-rich rock that in this area forms a layer 3 to 10 m thick. The laterite is about 30 to 65 million years old. It was formed when the climate was much warmer and wetter than it is today, and persistent rainfall weathered and oxidised the basalt and granite on the ground into ferricrete and laterite.

Cultural: The discovery of gold in the region saw the town of Sandstone rise out of the hot dirt in 1906. Gold fever drew miners from all over the country, and miners, more often than not, were a thirsty bunch.

Joseph Kearney saw a hole in the market and set up Black Range Brewery on top of this beautiful piece of breakaway laterite in August 1907. It’s elevated position made it visible up to 20km away – an alluring site for many a gold miner.

Black Range Brewery was a modern affair when it opened in August 1907 with water drawn from a nearby well and pumped into the brewery. The beer was stored in barrels inside the cellar, a massive tunnel blasted deep into the rock with dynamite at the face of the breakaway.

Black Range beer was sold to hotels throughout the district and the Brewery enjoyed a few years of prosperity before the arrival of the railway line and new sources of beer in 1910. All that remains of the brewery is the tunnel.

Shoemaker Crater is one of Australia’s largest and potentially oldest impact structures.

Estimates for Shoemaker Crater’s age range from 1,300 to 568 million years but it happened so long ago that, from ground level, you might be forgiven for thinking a meteorite never landed here. Satellite imagery, however, shows a different view.

The A – B – C of Shoemaker Crater

Abiotic: The prominent ring-like topographic feature, easily seen in satellite images, lies on the boundary between the Palaeoproterozoic Earaheedy Basin and the Archaean Yilgarn Craton which is the bulk of Western Australia’s land mass.

Research at Shoemaker Crater has revealed shatter cones and shocked quartz, confirming it to be an impact structure.

The central part of the crater is about 12km in diameter and is surrounded by an inner ring and an outer ring of Archaen Granite and sedimentary rocks that extend to a diameter of about 30km.

The area contains a number of seasonal salt lakes, being Lake Teague, Lake Nabberu, and Lake Shoemaker.

Biotic: The country surrounding Wiluna and the Canning Stock Route has significant mammal and reptile species, including the greater bilby, great desert skink and the black flanked rock wallaby to name a few. Many of these species are endangered but survive and shelter in the rocky hills and ranges.

The most widespread vegetation is spinifex grassland, and there are many types of woodlands including mulga, desert oak and eucalyptus.

Cultural: Extending over three pastoral leases, the crater was originally known as the Teague Ring but was renamed in 1988 to honour esteemed planetary geologist, Eugene Shoemaker and his wife Carolyn, who were critical in scientifically assessing Australia’s impact craters.

Shoemaker Crater is situated on private land and is not open to visitors but you can visit the Canning-Gunbarrel Discovery Centre in Wiluna to learn more.

This 100m long tunnel was dug in search of gold with only pick, shovels and rudimentary blasting skills – but all that effort didn’t lead to much of a payoff.

Five hundred and fifty tonnes of rock was excavated in 1896 but only three kilograms of gold were found in the area.

The A – B – C of Jokers Tunnel

Abiotic: While the town of Yalgoo sits on the Yalgoo–Singleton greenstone belt, which is rich in iron, zinc, copper, gold, silver and lead the tunnel itself had little value in it.

Biotic: Most of the gold mines in Yalgoo have shut down but you can find gold of a different kind in the area. At least seven species of acacia – otherwise known as wattle – grow here. In the spring their golden flowers erupt in a dazzling display of colour, drawing a whole host of brightly coloured birds like thornbills, honeyeaters and fairy-wrens to feed and nest in their branches. The tunnel itself serves as a place for animals to avoid the sun – so keep a look out for snakes and bats seeking shelter inside the tunnel.

Cultural: Yalgoo became a gold rush settlement in the 1890s, swelling the population to 2,300 people by 1896. No one is quite certain where the tunnel got its name from. Some believe it was named after William Nottle’s nearby gold mine, popularly known as Joker. Others believe it was named after the Jokers Mining Syndicate who dug it. And then there are those who think the whole thing was just one big joke on investors as prospectors tried every trick in the book to make a living.

At 24m in diameter and 3m deep, Dalgaranga Crater is the smallest of Australia’s 27 confirmed impact craters.

The crater’s age is not known but it could be as old as 25,000 years or as young as 3,000 years, which would make it the youngest crater in Australia and among the ten youngest known craters in the world.

Dalgaranga Crater is a State Geoheritage Reserve (R28497). Visitors are asked to consult with the Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety before visiting the site.

For conservation and safety reasons, please do not walk down into the crater

The A – B – C of Dalgaranga Crater

Abiotic: Discovered in 1921, Dalgaranga Crater was one of the first impact structures recognised in Australia and the only one to be formed on land by a mesosiderite (stony-iron meteorite). These rare meteorites consist of meteoric iron (iron and nickel) and silicates (minerals made of silicon and oxygen). The meteorite exploded on impact with erosion leaving behind only fragments of iron. The meteorite’s mass is estimated to have been between 500 and 1000 kg. Due to the crater being higher on one side than the other, scientists believe the meteorite slammed into the earth from the south-southeast at a low angle.

Biotic: A large mulga bush was growing in the crater centre before being cut down in 1959 to count the growth rings finding that the tree had germinated in 1905. The tree had germinated on top of a layer of breccia fill, which along with an examination of the rocks walls of the crater proved conclusively that the age of the crater far exceeded the age of the tree.

Cultural: An Aboriginal stockman named Billy Seward found Dalgaranga Crater in 1921 after nearly riding his horse into the hole while mustering cattle. The manager of Dalgaranga Station, Gerard Wellard recognised it as a probable impact crater and collected meteorite fragments which were eventually sent to the Department of Mines – it was not until 1938 that the first scientific mention was made of the crater with further significant studies taking place in 1959, 1963 and 1986.

Come see WA’s only working gold battery!

Open daily from 1 August to mid-October. Call Paynes Find Gold Battery and Museum on (08) 9963 6513 for more information.

The A – B – C of Paynes Find Battery

Abiotic: The gold that Thomas Payne and others found – and continue to find – rose out of ancient igneous rock. Gold deposits form relatively deep within the Earth, where quartz veins carrying primary or reef gold crosscut the greenstone–granite belts of this region. Weathering and erosion over millions of years brought gold nuggets to the Earth’s surface, making them easier for prospectors to find.

Biotic: Gold is not the only treasure to be found in and around Paynes Find. From late July to September, the region’s wildflowers burst out of the soil in a vibrant display of colour. Brightly coloured everlastings, native foxgloves, wild pomegranate, blue cornflowers and the distinctive wreath flowers make Paynes Find a goldmine for nature lovers.

Cultural: Paynes Find Battery was commissioned in 1911 as a State-run facility. It operated until 1986, crushing 70,000 tonnes of ore for 70,000 ounces of gold, before changing to private hands. You can still visit the gold-crushing plant and explore the display centre next door to learn about the gold mining process in the early 1900s.

Download the Murchison GeoRegion app for detailed information on the go!

The free app is your guide to this unique self-drive trail that focuses on some of the ancient natural and cultural wonders of WA.

Download the app to:

- plan out your trip before you leave

- learn more about the sites along the trail

- learn more about the region’s towns and services

- keep a record of your daily photos, videos, audio and written notes while you’re discovering the Murchison GeoRegion.

Available from where you download your apps.